Practice Essentials

A prostate biopsy is a procedure used to obtain tissue samples from the prostate gland in order to detect cancer. The biopsy is best performed with a spring-driven needle core biopsy device (or biopsy gun). Transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) is used to guide the biopsy needle.

Indications and contraindications

No prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value can establish with absolute certainty whether a patient has prostate cancer. Thus, the decision to proceed with prostate biopsy must be individualized. Urinary biomarkers have been shown to be useful in identifying patients at risk for prostate cancer prior to the initial biopsy. [1]

Even more difficult is the decision to perform a repeat biopsy. Patients with atypical small acinar neoplasia have an absolute indication for repeat biopsy soon after the initial biopsy. However, patients with focal high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) do not need to undergo automatic biopsy, because they are not at significantly higher risk for prostate cancer. By contrast, patients with multifocal HGPIN are at significant risk for prostate cancer and should undergo delayed interval biopsy every 3 years as long as they remain healthy. Patients who have persistently abnormal or rising PSA levels or very low percentages of free PSA (< 13%) are at some risk for harboring unrecognized prostate cancer and thus should be considered for repeat biopsy.

Contraindications for prostate biopsy include the surgical absence of a rectum or the presence of a rectal fistula.

Possible complications

The complications encountered after TRUS biopsy are commonly minor and self-limited, including mild hematuria, hematospermia, and transient rectal bleeding. Urinary tract infection is another frequently noted complication of prostate biopsy. [2]

Prevention of complications

The recommended antibiotic prophylaxis regimen consists of a single dose of a fluoroquinolone and a single dose of gentamicin. Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be discontinued for 5-7 days prior to the biopsy.

Background

This topic addresses indications for, preparation for, and performance of prostate biopsy—in particular, transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS)-guided biopsy of the prostate gland. [3] Although a number of different methods may be used to perform TRUS-guided prostate biopsy, the authors find that those described in this topic facilitate mastery of this procedure.

The basics of office-based procedures such as this are easily overlooked in urology training. Mastery of such seemingly simple procedures sometimes eludes the urology resident during times when the spotlight may be on major surgery. However, the increasing focus on office-based procedures, combined with the observation that large numbers of urologists now function primarily in an ambulatory setting, makes facility with such procedures an increasingly important part of urologic specialty care.

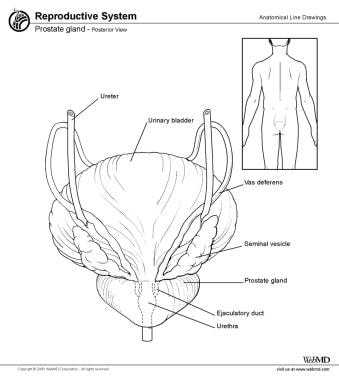

Relevant anatomy

A normal prostate gland (see the image below) is approximately 20 g in volume, 3 cm in length, 4 cm wide, and 2 cm in depth. As men get older, the prostate gland is variable in size secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. The gland is located posterior to the pubic symphysis, superior to the perineal membrane, inferior to the bladder, and anterior to the rectum. The base of the prostate is in continuity with the bladder and the prostate ends at the apex before becoming the striated external urethral sphincter. The sphincter is a vertically oriented tubular sheath that surrounds the membranous urethra and prostate. For more information about the relevant anatomy, see Prostate Anatomy and Seminal Vesicle Anatomy.

See Prostate Cancer: Diagnosis and Staging, a Critical Images slideshow, to help determine the best diagnostic approach for this potentially deadly disease.

Also, see the Advanced Prostate Cancer: Signs of Metastatic Disease slideshow for help identifying the signs of metastatic disease.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications for prostate biopsy are not set in stone. Initially, patients with a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value higher than 4.0 ng/mL were believed to have an absolute indication. Biopsy typically was also recommended for patients with suspicious findings on digital rectal examination (DRE).

However, the current established practice is that no PSA value exists that can establish with absolute certainty whether a patient does or does not have prostate cancer. Thus, the decision whether to proceed with prostate biopsy must be individualized in every case. Nomograms and predictive models have been developed to assist in this decision, but none have been able to provide a definite go/no go decision.

The introduction of markers (eg, prostate cancer antigen 3 gene [PCA3]) is an advantage of a nomogram or risk calculator over a PSA cut-point. Urinary PCA3 has been shown to be a useful tool in identifying patients at risk for prostate cancer prior to initial prostate biopsy. [4]

Even more difficult is the decision whether to perform a repeat biopsy. [5, 6] Patients with atypical small acinar neoplasia (ASAP) essentially have an absolute indication for repeat biopsy within a brief period after the initial biopsy. However, the situation is different for patients with high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN).

In the past, automatic repeat biopsy was recommended for patients with HGPIN. However, it is now generally considered that patients with focal HGPIN do not need to undergo automatic biopsy, because they are not at significantly higher risk for prostate cancer in the future. By contrast, patients with multifocal HGPIN are at significant risk for prostate cancer in the future; therefore, they should undergo delayed interval biopsy every 3 years as long as they remain healthy. [7, 8, 9, 10]

Patients who have persistently abnormal or rising PSA levels or very low percentages of free PSA (< 13%) are at some risk for harboring unrecognized prostate cancer and thus should be considered for repeat biopsy. [11] However, if a repeat biopsy is performed and it is negative, the likelihood of finding clinically significant prostate cancer in the future is very low, and a high threshold should be maintained for recommending further biopsy.

Contraindications for prostate biopsy include the surgical absence of a rectum or the presence of a rectal fistula.

Technical Considerations

Best practices

Today’s typical patient justifiably expects to undergo minimal pain and to be treated with respect for his or her privacy and modesty. Patient comfort is paramount to successful use of TRUS and prostate biopsy. This begins with the room setup. Respect for modesty is not only medicolegally advisable but also, and more importantly, the right thing to do. Using sheets to cover the legs allows the patient to feel some control over an embarrassing situation.

The examining room layout should minimize the chance that someone opening the door will be able to see the patient in a compromising position. Ideally, doors open in a manner that puts them between the person or persons entering and the patient until they have opened completely. This increases the time available for visitors to stop and leave if they find they are entering the wrong room (or the right room at the wrong time). Placing curtains in front of the door helps with this and undoubtedly makes the patient feel less vulnerable.

When possible, the examining table should be placed so that a patient who is in an exposed position is not situated in such a way that private body areas are visible from the door. The temperature should accommodate the comfort of the partially clothed patient.

Lubrication for urologic instruments is vital. The value of anesthetic-based lubricants has not been definitively demonstrated, but the role of lubrication to minimize the shearing forces of friction against rectal mucosa is undeniable. The authors use water-based lubricants (eg, KY Jelly) for TRUS because nothing has been demonstrated to provide better protection from pain.

Modern transrectal ultrasound probes are relatively small (often no larger than an examining finger) and thus are easily tolerable by most patients. Adequate (even abundant) lubrication minimizes the coefficient of kinetic friction and shearing forces against the anus. Given that attempts at anal mucosa and sphincteric anesthesia have yielded mixed results, lubrication and gentle technique remain the mainstays of comfort measures.

For patients with anorectal pain issues, application of Hurricaine or Urojet lubrication appears to decrease the pain of probe placement; however, it adds some discomfort in the course of its own application. Consequently, such lubrication is rarely used in the authors’ practice.

Complication prevention

Antibiotic prophylaxis

The authors have found no statistically significant difference in complications between a single dose of a fluoroquinolone and a 3-day course of antibiotics plus enema. The single-dose regimen has the advantage of ensuring full patient compliance, which cannot be guaranteed by more protracted courses requiring actions that must occur outside the clinic setting (eg, additional antibiotic doses and enemas).

Moreover, the single-dose fluoroquinolone regimen potentially minimizes the risk of emergence of resistant strains that may arise with unnecessarily prolonged courses of antibiotics. Finally, it saves considerable discomfort and some of the costs associated with more complex approaches that have shown no clear evidence of benefit.

Nevertheless, given the increase in microbial resistance to fluoroquinolones, the authors now recommend adding a single dose of gentamicin. The dose should be approximately 1 mg/kg, rounded to the next highest 40-mg vial measurement. Thus, for example, a 90-kg man should receive 120 mg of gentamicin.

Antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy

Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be discontinued for 5-7 days prior to the biopsy. In patients with coronary artery stents, aspirin should be continued to prevent stent thrombosis. Anticoagulation should be stopped for 5-7 days prior to biopsy or with an international normalized ratio of 1.5 or lower. However, in patients with a high risk of coagulopathies, heparin therapy should be started. [12]

-

Prostate gland.